Not all Sculptors are Prophets

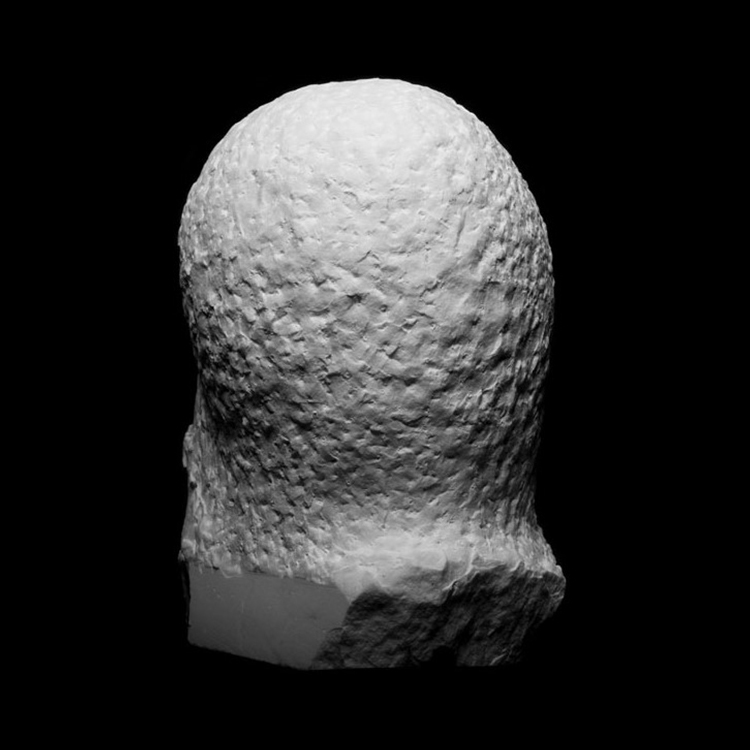

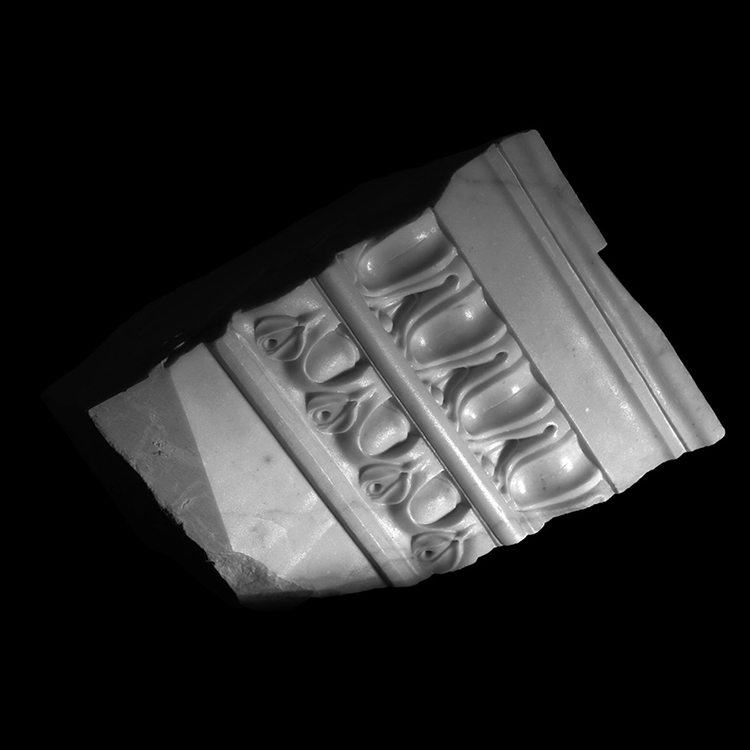

At its core, stone carving can be defined as an act of removal of stone from a larger block. Traditionally, removal is achieved using a hammer and a chisel, but other means can be applied as well, like those offered by new technologies such as CNC routers – the methods are countless.

Broadly speaking, any stone manmade artefact which results from a deliberate removal of material from a larger mass, and which has no utilitarian purpose in everyday life, can be regarded as sculpture.

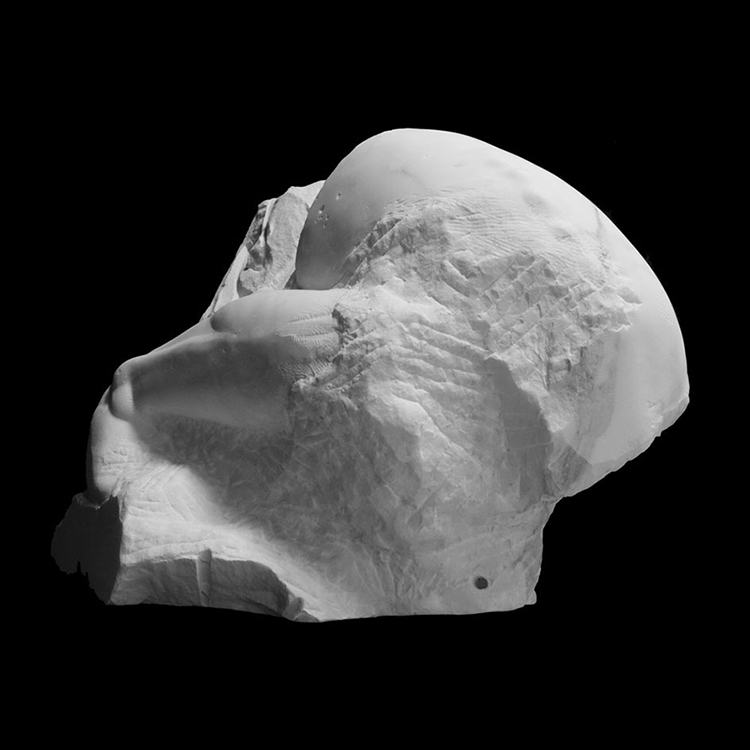

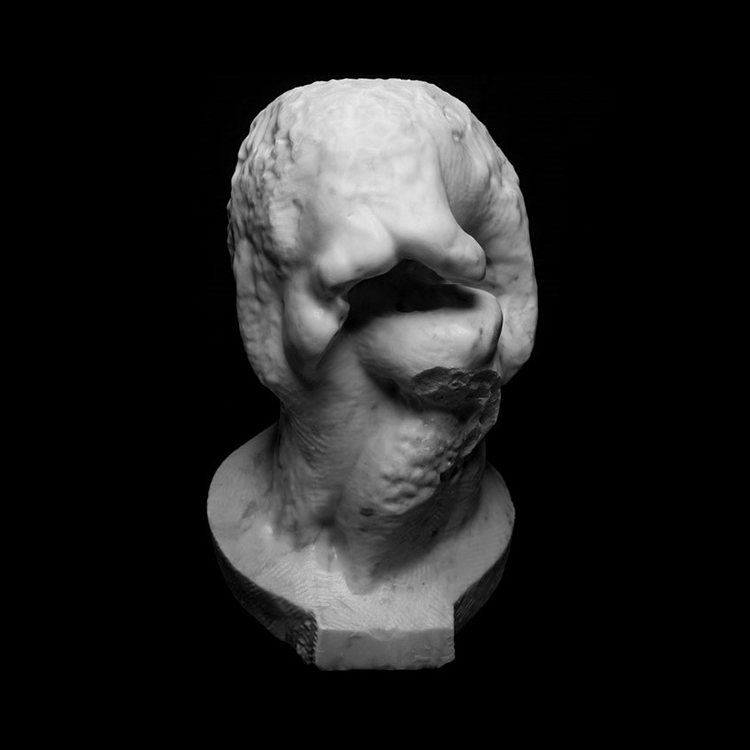

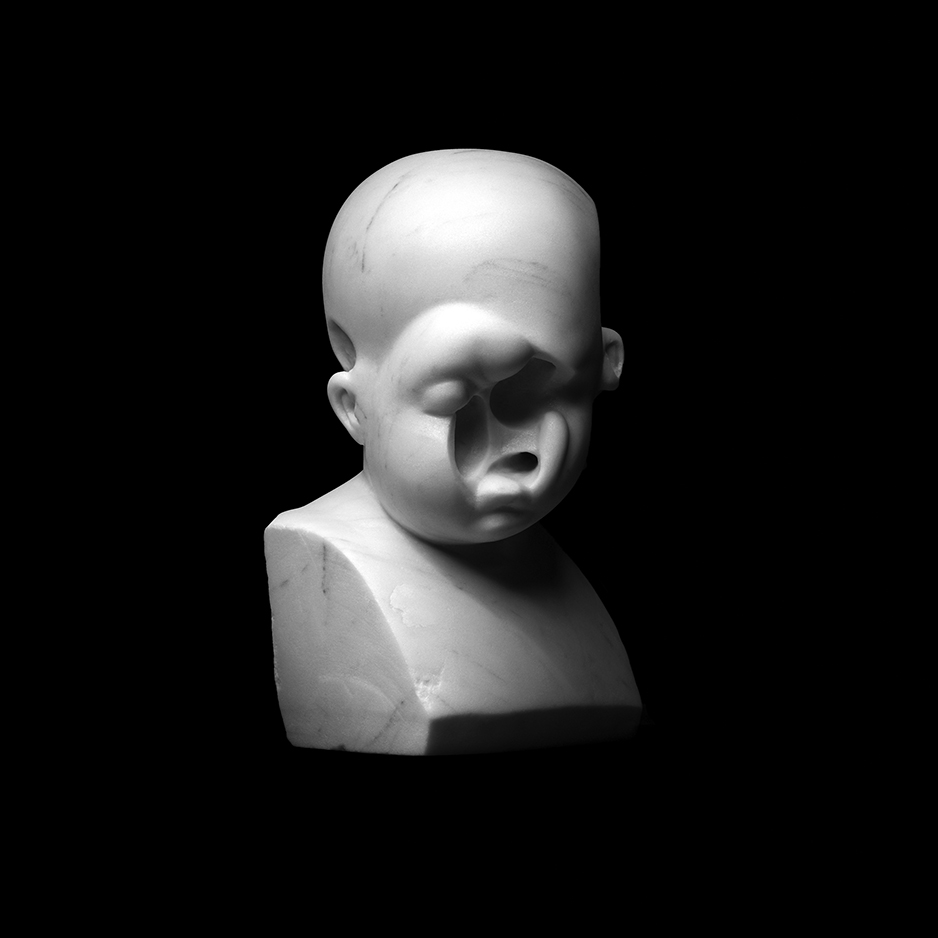

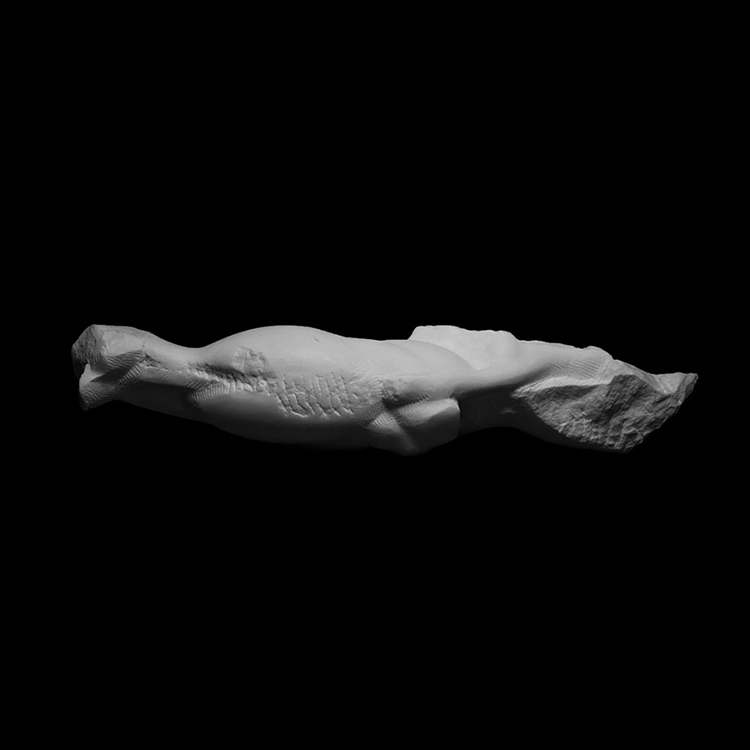

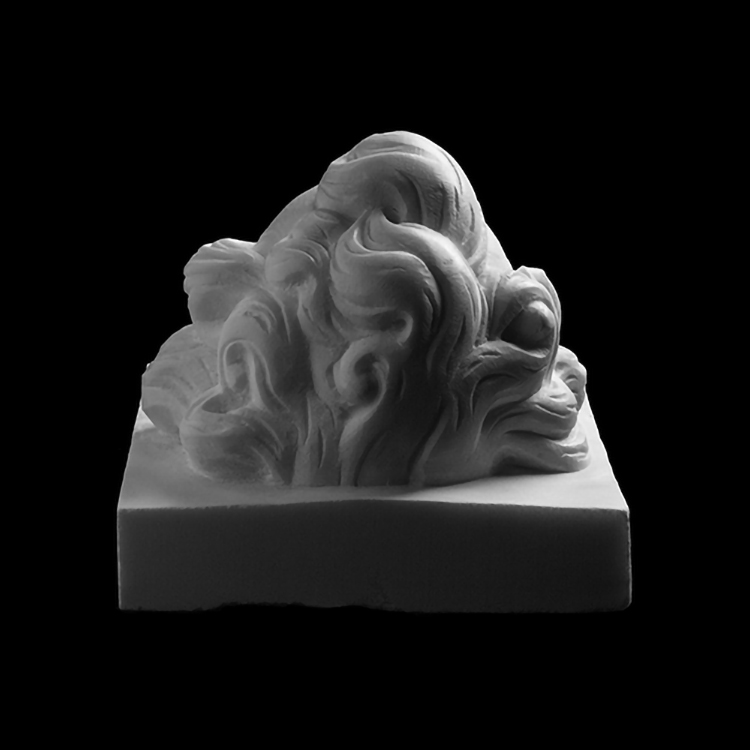

Classical sculpture is characterized by a shape in the positive. In academic terms, we refer to the tension of volumes pushing outwards from within the form. Before the arrival of 20th century sculptural concepts, sculpture was a matter of positive, palpable volumes in space. The classical quest to imitate nature – and god – motivated artists to achieve a divine-like status by pursuing a perfect representation of man – in the positive. The adjective “divine” was reserved to only a few exceptional artists who displayed an innate talent in shaping a human form out of inanimate material such as stone.

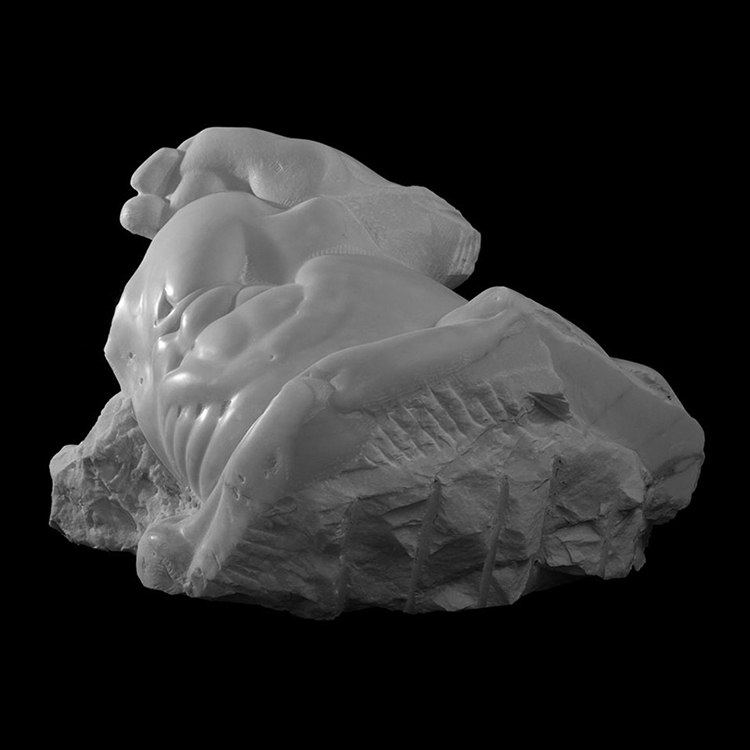

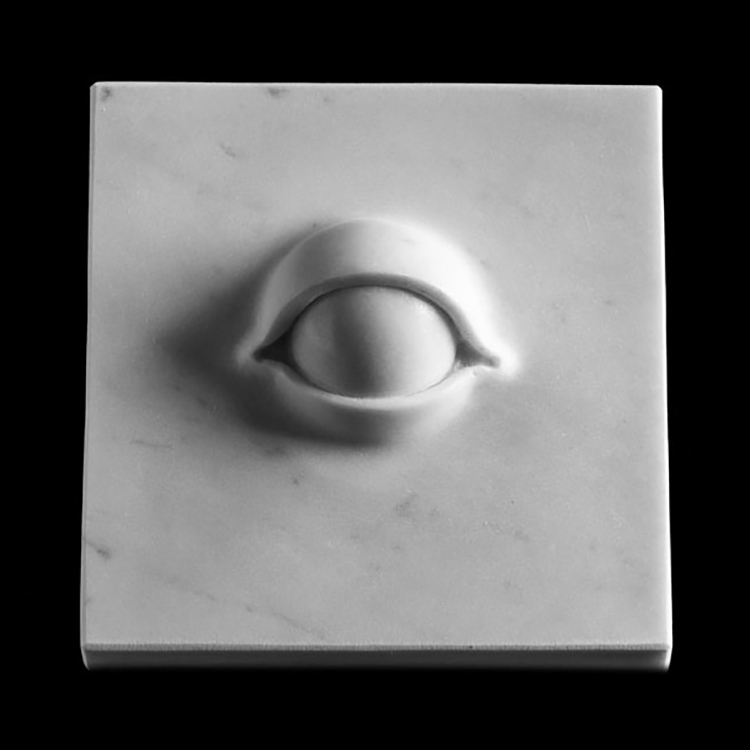

Revolutionary sculptors such as Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth introduced the concept of negative shapes and pointed out that these too are sculptural elements and presented them as the main subject in their sculpture. Contemporary artists such as Anish Kapoor capitalize on the concept of negative shapes., as seen in his concave works (or something along these lines).

Undoubtedly, the discoveries in physics at the beginning of the 20th century (black holes, anti-matter, etc.) played a pivotal role in informing many artistic expressions. It is perhaps with the advent of such new insights that sculpting shapes in the negative can also be associated with the divine. It comes as no surprise that, driven by their mimetic desire in a new attempt to reach the divine, artists started to fashion negative shapes in stone.

Little did they know, they were imitating a behaviour displayed much earlier by another group of people.

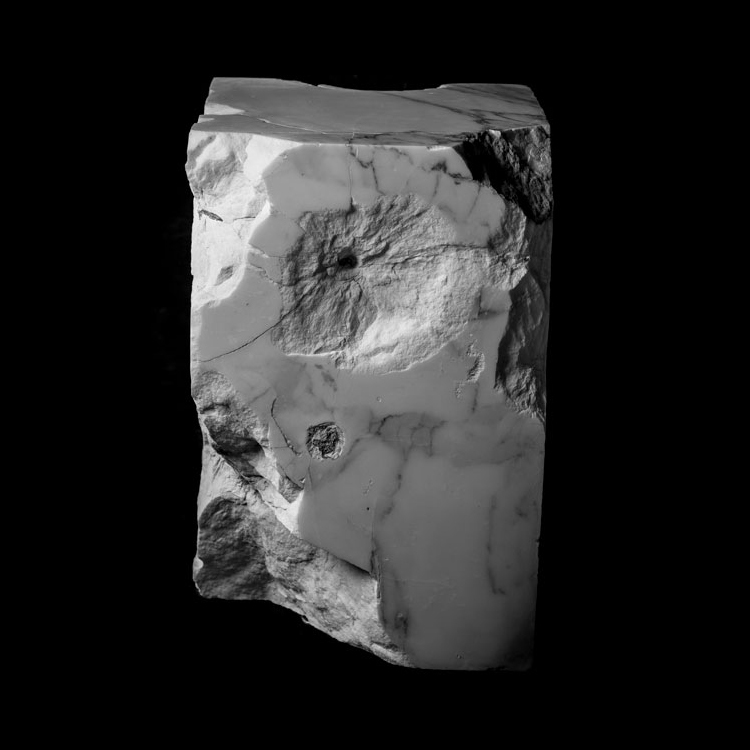

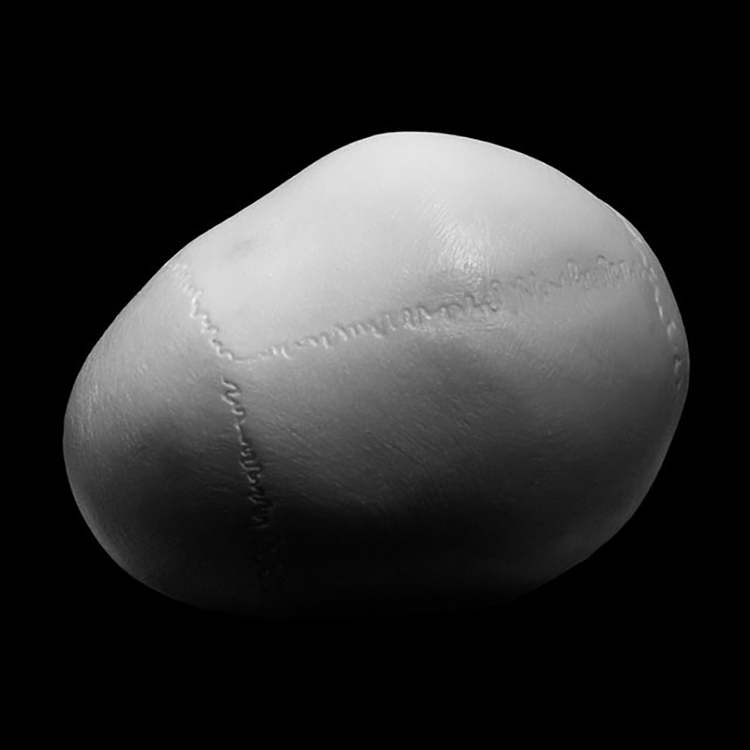

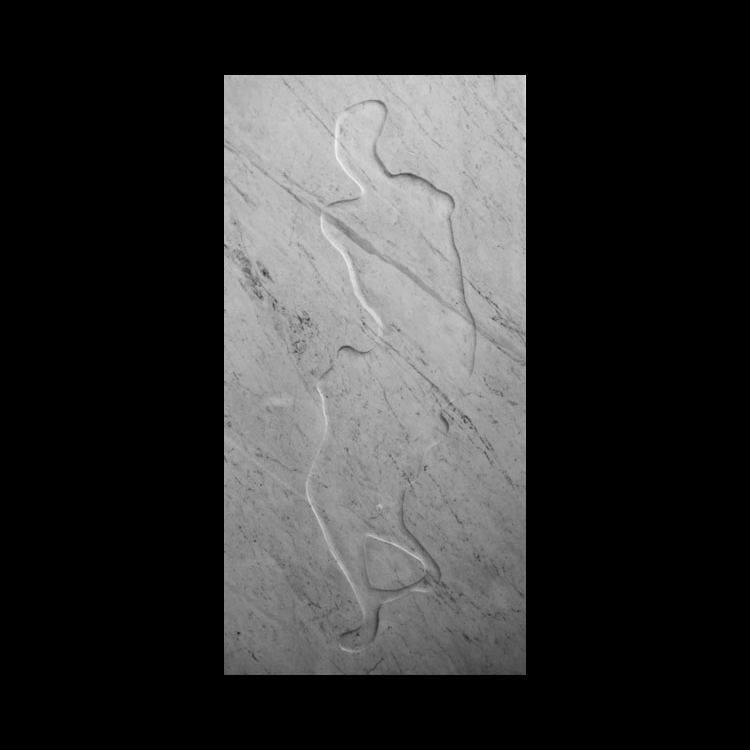

According to the legend, after Buddha attained enlightenment, he flew to Sri Lanka and left his footprint on a rock atop Sri Padaya, a tall conical mountain located in central Sri Lanka. Hindu tradition refers to the same footprint as that of the Hindu deity Shiva. Christian and Islamic traditions assert that it is the footprint of Adam, left from when he first set foot on Earth after he had been exiled from paradise – hence the name of the mountain, Adam’s peak.

On the way to his crucifixion, while carrying his cross, Jesus stumbled and leaned on a wall to keep from falling. Allegedly, this action left a hand-shaped depression into the stone. It is still visible today in Jerusalem. Another anecdote tells how Jesus, while fasting for forty days on the Mount of Temptation, regularly used to kneel on one specific stone for prayers. This stone is now conserved at the Monastery of the Temptation near Jericho, and it bears the imprint of Jesus’s knees. At a day’s walk away, at the Chapel of the Ascension in Jerusalem, there are a pair of footprints embedded into a stone. They are reputed to be those of Jesus made at the time of his Ascension into heaven. Similarly, the church of Saint Sebastian outside Rome’s walls houses a stone which, according to tradition, bears the footprints of Jesus when he appeared to Saint Peter on the Appian Way.

The Maqam Ibrahim (“Abraham’s place of standing”) is a rock kept in a crystal dome next to the Ka’bah in Mecca. The footprint in it is believed, by Muslim tradition, to have been made by Abraham when he was lifting stone blocks to build the Ka’bah. Another Islamic tradition holds that whenever the Prophet Muhammad stepped upon a stone or rock, his blessed foot left an imprint. The most famous of these imprints is found in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. From this stone, the Prophet set off to the heavens. During this ascension, the rock itself started to rise at the southern end, but was held down by the Archangel Gabriel. Some marks on the western side of the rock are said to be the fingerprints of Gabriel. While at the Qubbat al-Sanaya (the Dome of the Front Teeth), a mark on a stone wall is said to have been made when Muhammad was attacked. He lost a tooth during the incident, and when the tooth fell, it left a mark onto the stone wall.

The Devil has also left his marks. After realizing he had been victim of trickery by the builder of the Frauenkirche church in Munich, the devil stood at its entrance, stomping his foot furiously and leaving a footprint that remains visible in the church’s entrance today.

The veracity of the above-mentioned artefacts is not proven. However, indulging in good faith, we can claim that the prophets’ habit of interacting with stone presents some unequivocable sculptural qualities.

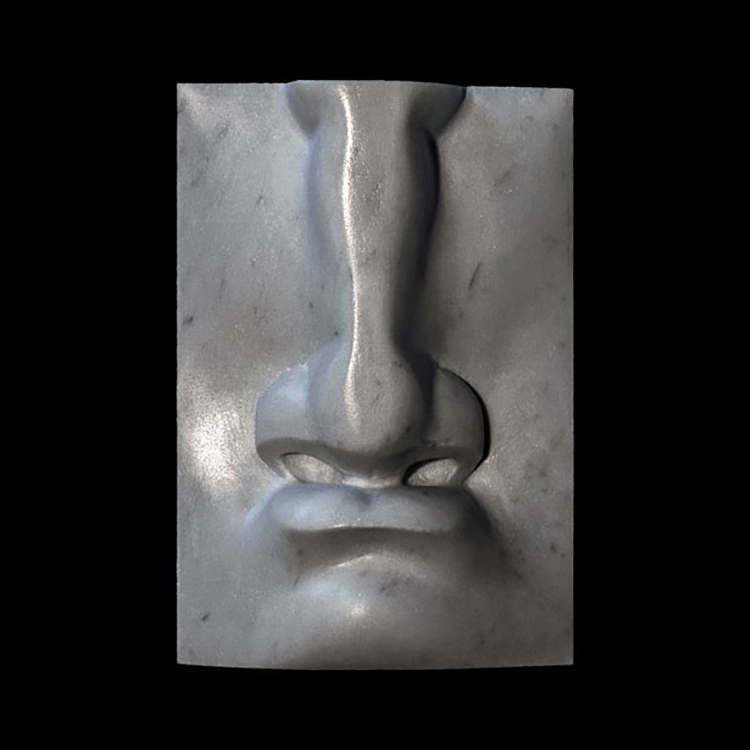

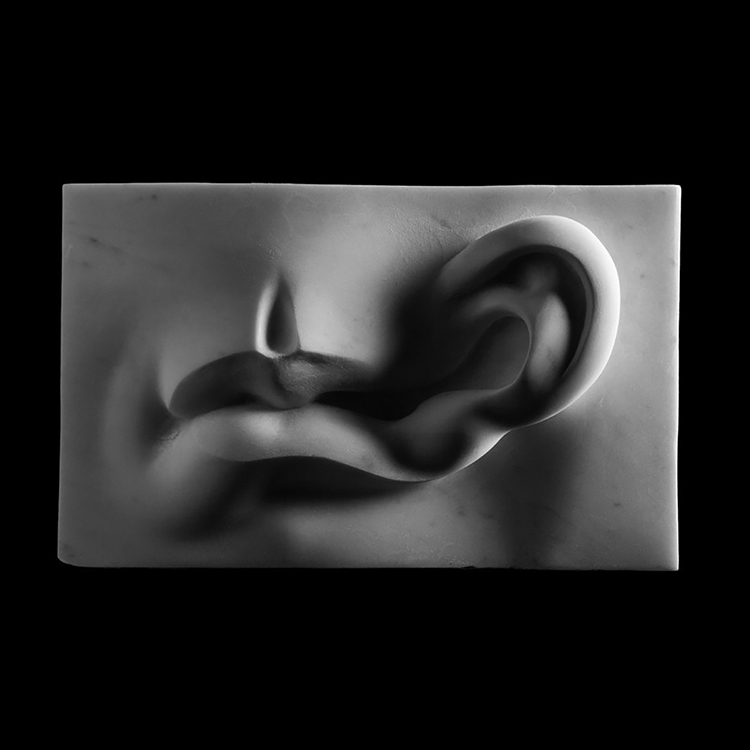

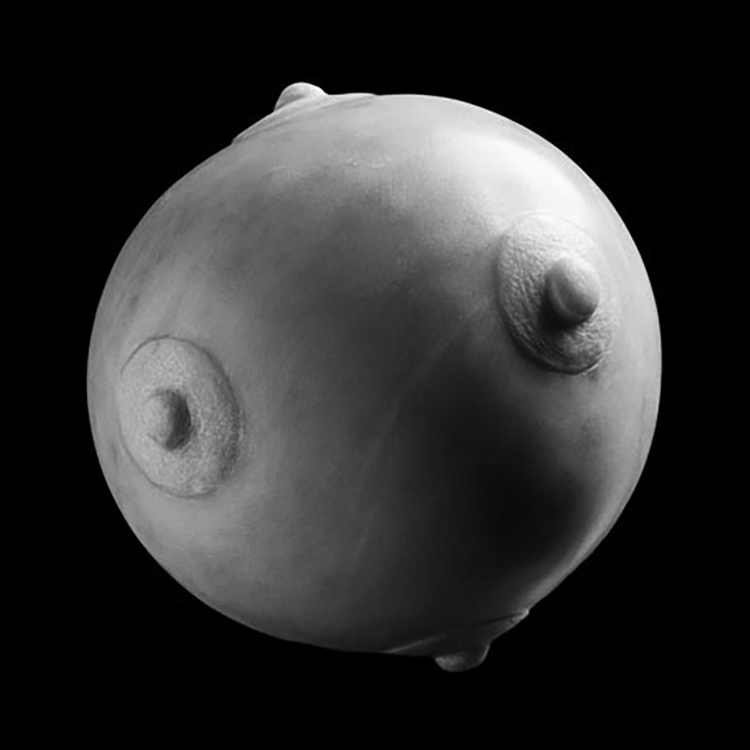

The marks left on stone by prophets and divinities, often imprints in the negative, can be interpreted as sculptural interventions like those of Moore, Hepworth and Kapoor. They are far from abstract shapes, in contrast. They present clear figurative elements in the form of specific body parts. Unlike classical in sculptures, where the body is presented by shapes in the positive as if it is emerging from within the stone, here, the impressions of body parts in the negative tend to suggest an inclination to merge back into the stone.

This behavior repeats in human interactions with religious stone artefacts. Mimicking the actions of the prophets, humans place their body parts in the marks left by the prophets, as if they seek to fill that gap. Over the course of the centuries, these rituals slowly contributed to pushing the imprint even further into the stone. They continually reinforced the evidence on which religions are so dependent on to prove their legitimacy. The longer one believes in something, and acts according to the recommended liturgy, the more that belief is imprinted and embedded into reality.